A blood test could predict the risk of Alzheimer’s disease

A new blood test might reveal whether someone is at risk of getting Alzheimer’s disease.

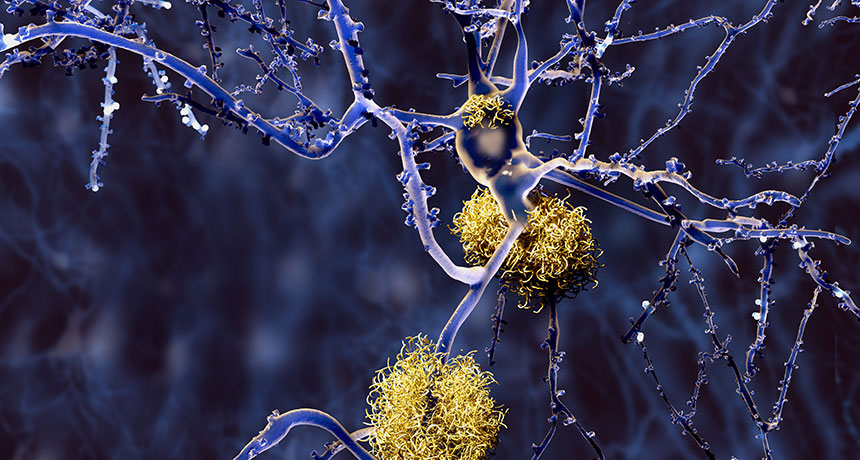

The test measures blood plasma levels of a sticky protein called amyloid-beta. This protein can start building up in the brains of Alzheimer’s patients decades before there’s any outward signs of the disease. Typically, it takes a brain scan or spinal tap to discover these A-beta clumps, or plaques, in the brain. But evidence is growing that A-beta levels in the blood can be used to predict whether or not a person has these brain plaques, researchers report online January 31 in Nature.

These new results mirror those of a smaller 2017 study by a different team of scientists. “It’s a fantastic confirmation of the findings,” says Randall Bateman, an Alzheimer’s researcher at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, who led the earlier study. “What this tells us is that we can move forward with this [test] approach with fairly high confidence that this is going to pan out.”

There’s currently no treatment for Alzheimer’s that can slow or stop the disease’s progression, so catching it early can’t currently improve a patient’s outcome. But a blood test could help researchers more easily identify people who might be good candidates for clinical trials of early interventions, says Steven Kiddle, a biostatistician at the University of Cambridge, who wasn’t part of either study.

Creating such a test has been challenging: Relatively little A-beta floats in the bloodstream compared with how much accumulates in the brain. And many past studies haven’t found a consistent correlation between the two.

In the new study, researchers used mass spectrometry, a more sensitive measuring technique than used in most previous tests, which allowed the detection of smaller amounts of the protein. And instead of looking at the total level of the protein in the blood, the team calculated the ratios between different types of A-beta, says coauthor Katsuhiko Yanagisawa, a gerontologist at the National Center for Geriatrics and Gerontology in Obu, Japan.

He and his colleagues analyzed brain scans and blood samples from a group of 121 Japanese patients and a group of 252 Australian patients. Some participants had Alzheimer’s, some didn’t, and some had mild cognitive impairments that weren’t related to Alzheimer’s.

Using the ratios, the researchers found that they could discriminate between people who had A-beta plaques in the brain and those who didn’t. A composite biomarker score, created by combining two different ratios, predicted the presence or absence of A-beta plaques in the brain with about 90 percent accuracy in both groups of patients, the researchers found.

The new results are promising, Kiddle says, but the test still needs more refining before it can be used in the clinic. Another wild card: the cost. It’s still not clear whether the blood test will be more affordable than a brain scan or a spinal tap.