Nasty stomach viruses can travel in packs

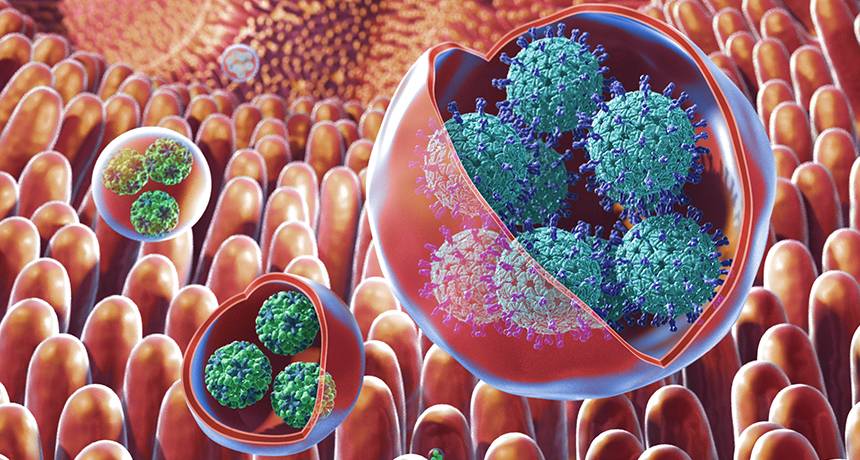

Conventional wisdom states that viruses work as lone soldiers. Scientists now report that some viruses also clump together in vesicles, or membrane-bound sacs, before an invasion. Compared with solo viruses, these viral “Trojan horses” caused more severe infections in mice, researchers report August 8 in Cell Host & Microbe.

Cell biologist Nihal Altan-Bonnet had been involved in discovering in 2015 that polioviruses can cluster together to invade cells in a petri dish. In the new study, Altan-Bonnet and a different group of colleagues find that transmission via virus clumps also occurs naturally with both rotavirus and norovirus, which can cause gastrointestinal illness.

The scientists first identified norovirus cluster vesicles in patients’ stool samples, which was “eye-opening,” says Altan-Bonnet, who works at the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md. “We can see these vesicles everywhere.”

Altan-Bonnet and her team infected live mice with either vesicle-packaged rotavirus or equal amounts of single virus particles. Vesicles were not only more successful in causing infections, they also caused infections that were more severe, the researchers found. In the mice, it took five times the amount of single virus particles to cause the same severity of infection as caused by the clustered viruses. It also took the mice two to four days longer to fight off the cluster-caused infections.

While the mice were sick, the researchers found viral clumps in their feces, showing that the vesicles were able to survive the harsh environment of the GI system unscathed. It’s still unclear, however, if the viruses remain inside the vesicles to invade cells, and if so, how.

The clusters act like a Trojan horse, Altan-Bonnet suggests. “The wooden horse would be the vesicle, and inside it you have all the soldiers.” She has several hypotheses for why viruses behave this way. Vesicles may help the viruses evade the immune system or replicate faster inside cells. “We really have to rethink the way we think about viruses,” she says.

Norovirus and rotavirus, which can be dangerous for children and the elderly, kill a combined total of about 265,000 children each year worldwide, mostly in developing countries (SN: 8/8/15, p. 5). The researchers hope the discovery of vesicle transmission will lead to better prevention methods and treatments, for example, by targeting the membranes containing the virus clusters.

Because the long-standing “dogma in the field” suggested viruses were transmitted individually, it’s not surprising that these vesicles were missed in earlier virus research, says Craig Wilen, a physician at the Yale School of Medicine who recently discovered what cells norovirus targets in mice (SN: 5/12/18, p. 14). “It’s probably been seen and just dismissed.”

Wilen says that there are still questions about viral clusters that need to be answered. For example, he says, “how does the virus escape the vesicle?” Other questions that remain include how the vesicle latches on to a cell’s surface, and what advantage the viruses actually get from packaging themselves together.