Why pandemic fatigue and COVID-19 burnout took over in 2022

2022 was the year many people decided the coronavirus pandemic had ended.

President Joe Biden said as much in an interview with 60 Minutes in September. “The pandemic is over,” he said while strolling around the Detroit Auto Show. “We still have a problem with COVID. We’re still doing a lot of work on it. But the pandemic is over.”

His evidence? “No one’s wearing masks. Everybody seems to be in pretty good shape.”

But the week Biden’s remarks aired, about 360 people were still dying each day from COVID-19 in the United States. Globally, about 10,000 deaths were recorded every week. That’s “10,000 too many, when most of these deaths could be prevented,” the World Health Organization Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said in a news briefing at the time. Then, of course, there are the millions who are still dealing with lingering symptoms long after an infection.

Those staggering numbers have stopped alarming people, maybe because those stats came on the heels of two years of mind-boggling death counts (SN Online: 5/18/22). Indifference to the mounting death toll may reflect pandemic fatigue that settled deep within the public psyche, leaving many feeling over and done with safety precautions.

“We didn’t warn people about fatigue,” says Theresa Chapple-McGruder, an epidemiologist in the Chicago area. “We didn’t warn people about the fact that pandemics can last long and that we still need people to be willing to care about yourselves, your neighbors, your community.”

Public health agencies around the world, including in Singapore and the United Kingdom, reinforced the idea that we could “return to normal” by learning to “live with COVID.” The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s guidelines raised the threshold for case counts that would trigger masking (SN Online: 3/3/22). The agency also shortened suggested isolation times for infected people to five days, even though most people still test positive for the virus and are potentially infectious to others for several days longer (SN Online: 8/19/22).

The shifting guidelines bred confusion and put the onus for deciding when to mask, test and stay home on individuals. In essence, the strategy shifted from public health — protecting your community — to individual health — protecting yourself.

Doing your part can be exhausting, says Eric Kennedy, a sociologist specializing in disaster management at York University in Toronto. “Public health is saying, ‘Hey, you have to make the right choices every single moment of your life.’ Of course, people are going to get tired with that.”

Doing the right thing — from getting vaccinated to wearing masks indoors — didn’t always feel like it paid off on a personal level. As good as the vaccines are at keeping people from becoming severely ill or dying of COVID-19, they were not as effective at protecting against infection. This year, many people who tried hard to make safe choices and had avoided COVID-19 got infected by wily omicron variants (SN Online: 4/22/22). People sometimes got reinfected — some more than once (SN: 7/16/22 & 7/30/22, p. 8).

Those infections may have contributed to a sense of futility. “Like, ‘I did my best. And even with all of that work, I still got it. So why should I try?’ ” says Kennedy, head of a Canadian project monitoring the sociological effects of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Getting vaccinated, masking and getting drugs or antibody treatments can reduce the severity of infection and may cut the chances of infecting others. “We should have been talking about this as a community health issue and not a personal health issue,” Chapple-McGruder says. “We also don’t talk about the fact that our uptake [of these tools] is nowhere near what we need” to avoid the hundreds of daily deaths.

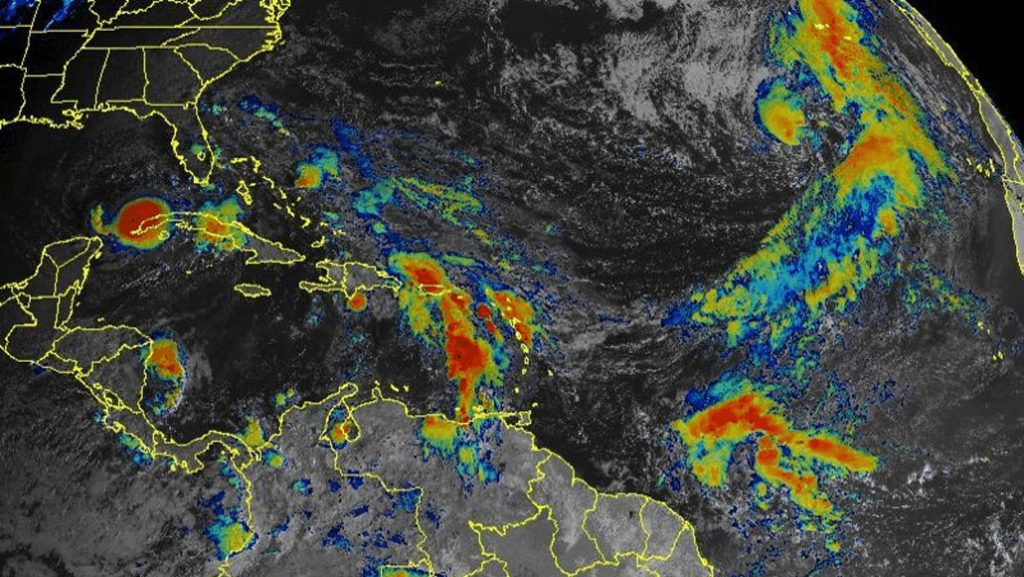

A lack of data about how widely the coronavirus is still circulating makes it difficult to say whether the pandemic is ending. In the United States, the influx of home tests was “a blessing and a curse,” says Beth Blauer, data lead for the Johns Hopkins University Coronavirus Resource Center. The tests gave an instant readout that told people whether they were infected and should isolate. But because those results were rarely reported to public health officials, true numbers of cases became difficult to gauge, creating a big data gap (SN Online: 5/27/22).

The flow of COVID-19 data from many state and local agencies also slowed to a trickle. In October, even the CDC began reporting cases and deaths weekly instead of daily. Altogether, undercounting of the coronavirus’s reach became worse than ever.

“We’re being told, ‘it’s up to you now to decide what to do,’ ” Blauer says, “but the data is not in place to be able to inform real-time decision making.”

With COVID-19 fatigue so widespread, businesses, governments and other institutions have to find ways to step up and do their part, Kennedy says. For instance, requiring better ventilation and filtration in public buildings could clean up indoor air and reduce the chance of spreading many respiratory infections, along with COVID-19. That’s a behind-the-scenes intervention that individuals don’t have to waste mental energy worrying about, he says.

The bottom line: People may have stopped worrying about COVID-19, but the virus isn’t done with us yet. “We have spent two-and-a-half years in a long, dark tunnel, and we are just beginning to glimpse the light at the end of that tunnel. But it is still a long way off,” WHO’s Tedros said. “The tunnel is still dark, with many obstacles that could trip us up if we don’t take care.” If the virus makes a resurgence, will we see it coming and will we have the energy to combat it again?