Cave-dwelling salamander comes pigmented and pale

Normal is the new strange for the world’s largest cave salamanders.

Biologists are thinking deep thoughts about why some of Europe’s olm salamanders living in darkness have (gasp!) skin coloring and eyes with lenses.

Most salamanders, of course, have skin pigments and grow adult eyes like other vertebrates. But after eons of cave life, olms (Proteus anguinus) have become mostly pinkish-white beasts, about 30 centimeters head to tail, that spend long lifetimes (maybe 70 years) slinking in cold, subterranean water.

Living at 11 to 12° Celsius, olms don’t mature sexually until about age 11 for males and 14 for females. Even then, they never really grow up, staying in water like giant larvae and keeping such youthful features as neck fluff gills into old age. “They look a little creepy, especially if you look at the skull,” says Stanley Sessions of Hartwick College in Oneonta, N.Y. Their blunt heads have no real upper jaw, and their adult eyes start to form but then regress to nubbins buried under skin.

These salamanders live frugally. They can go more than a year without eating. (Lilijana Bizjak Mali of the University of Ljubljana in Slovenia says a lab-dwelling olm survived even after more than 10 years without food.) Females take six-to-12-year breaks between laying eggs, which “develop extraordinarily slowly,” Sessions says. Recently laid olm eggs in Slovenia’s Postojna Cave took about seven weeks to start forming a nervous system; a common spotted salamander takes about one.

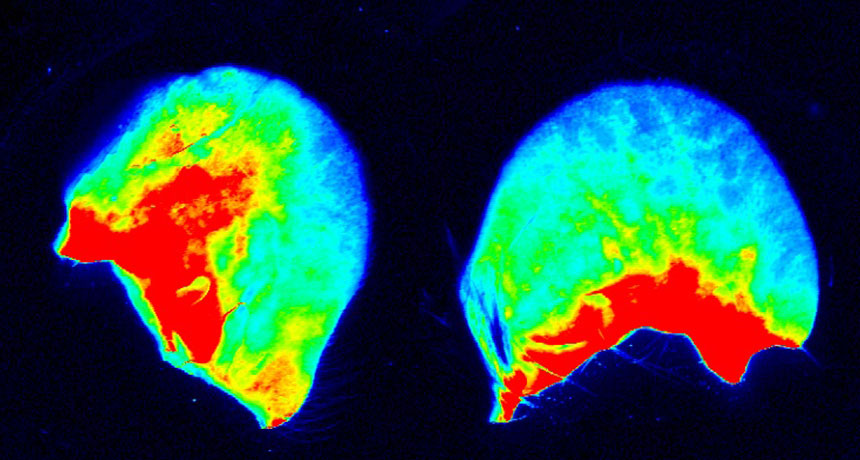

Among extreme cave-lifers, the oddballs are the more normal-looking salamanders (for now, called subspecies parkelj), with dark skin and better-developed eyes. For decades, biologists treated these curios as remnants of the most ancient olms that haven’t shed all their daylight ways. But rather than putting the dark salamanders at the base of the genealogical tree of olms, a genetic analysis places them higher among more recent, pale lineages.

“This forces you to consider that the black one probably evolved from white ancestors by reversing cave adaptations,” Sessions says. In evolution, “weirder things have happened.”