How fingerprints form was a mystery — until now

Scientists have finally figured out how those arches, loops and whorls formed on your fingertips.

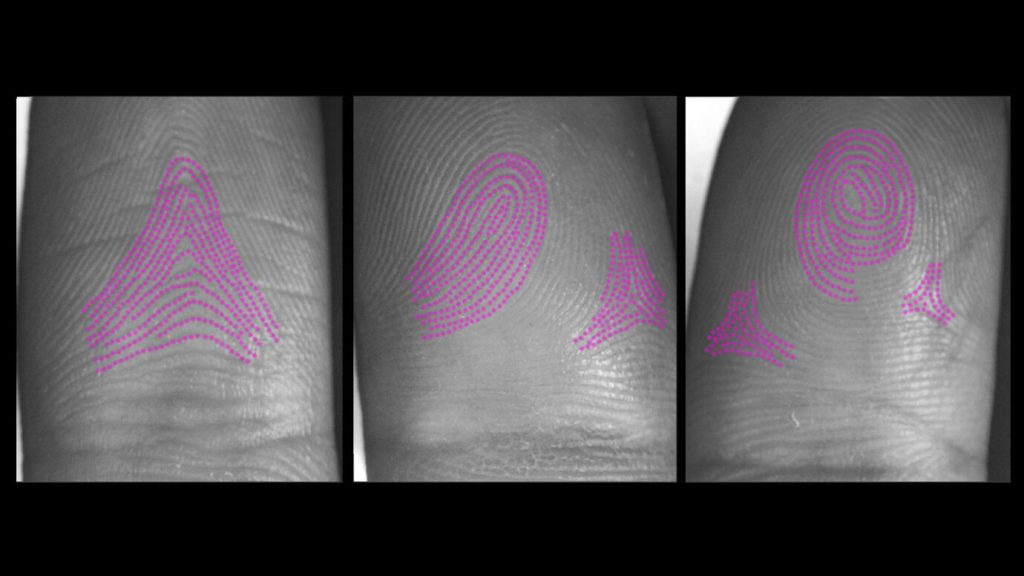

While in the womb, fingerprint-defining ridges expand outward in waves starting from three different points on each fingertip. The raised skin arises in a striped pattern thanks to interactions between three molecules that follow what’s known as a Turing pattern, researchers report February 9 in Cell. How those ridges spread from their starting sites — and merge — determines the overarching fingerprint shape.

Fingerprints are unique and last for a lifetime. They’ve been used to identify individuals since the 1800s. Several theories have been put forth to explain how fingerprints form, including spontaneous skin folding, molecular signaling and the idea that ridge pattern may follow blood vessel arrangements.

Scientists knew that the ridges that characterize fingerprints begin to form as downward growths into the skin, like trenches. Over the few weeks that follow, the quickly multiplying cells in the trenches start growing upward, resulting in thickened bands of skin.

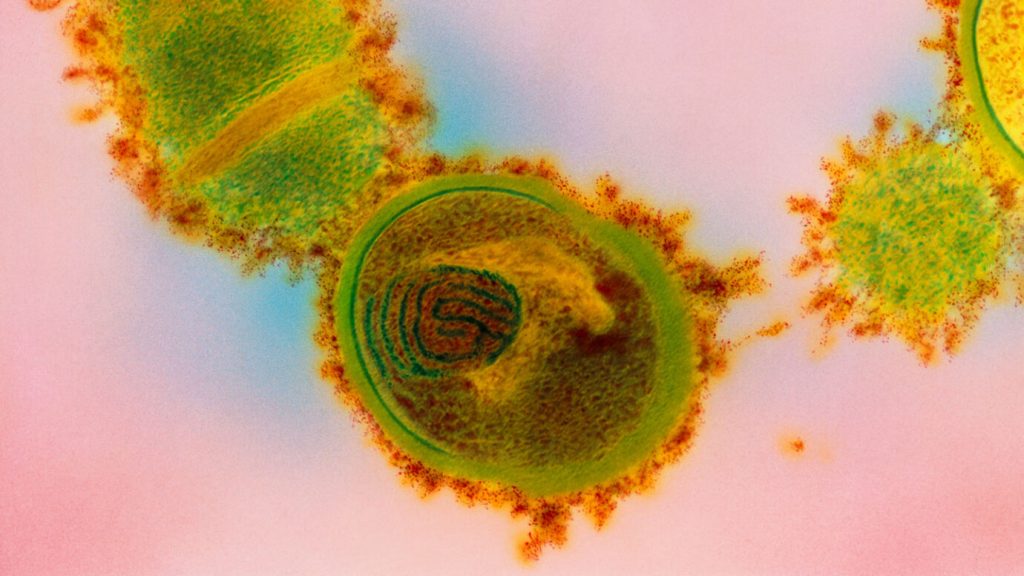

Since budding fingerprint ridges and developing hair follicles have similar downward structures, researchers in the new study compared cells from the two locations. The team found that both sites share some types of signaling molecules — messengers that transfer information between cells — including three known as WNT, EDAR and BMP. Further experiments revealed that WNT tells cells to multiply, forming ridges in the skin, and to produce EDAR, which in turn further boosts WNT activity. BMP thwarts these actions.

To examine how these signaling molecules might interact to form patterns, the team adjusted the molecules’ levels in mice. Mice don’t have fingerprints, but their toes have striped ridges in the skin comparable to human prints. “We turn a dial — or molecule — up and down, and we see the way the pattern changes,” says developmental biologist Denis Headon of the University of Edinburgh.

Increasing EDAR resulted in thicker, more spaced-out ridges, while decreasing it led to spots rather than stripes. The opposite occurred with BMP, since it hinders EDAR production.

That switch between stripes and spots is a signature change seen in systems governed by Turing reaction-diffusion, Headon says. This mathematical theory, proposed in the 1950s by British mathematician Alan Turing, describes how chemicals interact and spread to create patterns seen in nature (SN: 7/2/10). Though, when tested, it explains only some patterns (SN: 1/21/14).

Mouse digits, however, are too tiny to give rise to the elaborate shapes seen in human fingerprints. So, the researchers used computer models to simulate a Turing pattern spreading from the three previously known ridge initiation sites on the fingertip: the center of the finger pad, under the nail and at the joint’s crease nearest the fingertip.

By altering the relative timing, location and angle of these starting points, the team could create each of the three most common fingerprint patterns — arches, loops and whorls — and even rarer ones. Arches, for instance, can form when finger pad ridges get a slow start, allowing ridges originating from the crease and under the nail to occupy more space.

“It’s a very well-done study,” says developmental and stem cell biologist Sarah Millar, director of the Black Family Stem Cell Institute at the Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai in New York City.

Controlled competition between molecules also determines hair follicle distribution, says Millar, who was not involved in the work. The new study, she says, “shows that the formation of fingerprints follows along some basic themes that have already been worked out for other types of patterns that we see in the skin.”

Millar notes that people with gene mutations that affect WNT and EDAR have skin abnormalities. “The idea that those molecules might be involved in fingerprint formation was floating around,” she says.

Overall, Headon says, the team aims to aid formation of skin structures, like sweat glands, when they’re not developing properly in the womb, and maybe even after birth.

“What we want to do, in broader terms, is understand how the skin matures.”