How to trap sperm

New sperm-catching beads could someday help prevent pregnancy — or enable it.

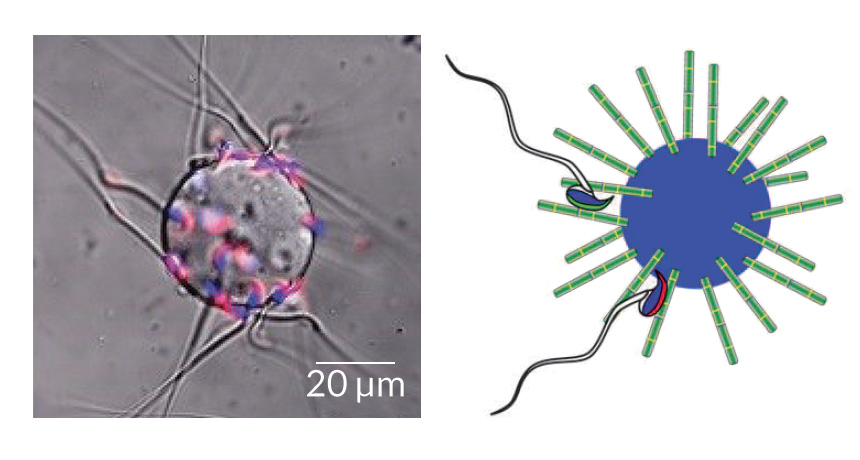

Researchers created microscopic polymer beads that mimic unfertilized eggs and trap passing sperm. The beads are coated in the sperm-binding section of a protein called ZP2. In mammals, ZP2 is found in membranes around unfertilized eggs; sperm must bind to the protein before entering the egg.

The beads could be used as short-term contraceptives, Jurrien Dean of the National Institutes of Health in Bethesda, Md., and colleagues report in the April 27 Science Translational Medicine. In the laboratory, human sperm attached to the beads within five minutes. The researchers then mixed 100,000 human sperm with 1.5 million beads and 28 mouse eggs containing human ZP2 proteins. After 16 hours, only one sperm reached an egg.

In another experiment, beads coated with mouse ZP2 delayed pregnancy when injected into the uteruses of mating female mice. Bead-free mice took just over 28 days, on average, to conceive and give birth; bead-treated mice didn’t have babies for nearly 73 days on average. The beads didn’t appear to cause swelling or damage, and treated mice were able to give birth again within five months.

The beads could also help combat infertility. In an egg-penetration test, researchers gently detached bead-captured sperm and pitted those sperm against a control batch of sperm that had not been exposed to the beads. More than half of eggs (mouse eggs with human ZP2) exposed to the bead-selected sperm ended up with three or more sperm attached to them; none of the eggs exposed to the control group snagged three or more sperm. In fact, the control group failed to penetrate 38 out of 50 eggs. So the beads could someday be used to select healthy sperm for assisted reproduction, the researchers say.

But it’s not clear if the ability to bind to ZP2 necessarily indicates a healthy sperm, says Andrew La Barbera, chief scientific officer of the American Society for Reproductive Medicine in Birmingham, Ala. “Sperm selection is a very complex undertaking because of the fact that sperm are very complex,” he says. “We don’t know what makes a good sperm.”

Contraception might be a more reasonable future use for the beads, although allowing fertilization of one in 28 eggs is underwhelming, La Barbera says. Birth control should be closer to 99.9 percent effective. “It only takes one sperm to fertilize an egg,” he says. Still, the beads’ performance at blocking pregnancy in mice seems promising, La Barbera says. Future experiments would need to determine if the beads are safe and effective in women, and how many beads are needed to prevent conception.

Dean notes that the study is a proof of principle. Many unknowns must be evaluated before using the beads for birth control, including the side effects of long-term use, he says. “Although promising, we are a long way from translating these basic laboratory observations into useful clinical applications that provide people with better reproductive choices.”